Studs Finder

As an artist working to enrich your soul through the sanctified ritual of creative endeavor, you inevitably face one eternal truth: Your old work sucks. I mean, it’s just butt-awful. What were you thinking when you whipped up that garbage? I find myself ashamed of your dark past. I don’t think we should see each other anymore.

Or perhaps I should say, as artists, we all get a lot better. And in getting better, we can see more clearly what miserable poo our earlier efforts were. If we could chart this progress as a continuous stream of youthful, blind ignorance to aged enlightenment, well, all would be hunky dory.

But no. Somehow, we’re still stupid. There are still days when our perceptions are clouded, our brains fogged, our attention spans disrupted by K-Pop or Joe Rogan, and we somehow fail to see the humiliating disaster we are scratching out on the paper (or, god forbid, on the iPad). We devolve into our youthful, deluded selves, believing, despite the evidence, that we are in the process of producing highly-polished perfection, as is our usual standard. If we’re lucky, we’ll wake up the next morning with clearer eyes, as if seeing an overnight guest drooling on the adjacent pillow, and wondering why we hadn’t noticed that unibrow the previous evening.

Well, I don’t know about you, but I’m lucky if I’m that lucky. More often, the revelation of my own hideous misjudgment takes years to strike. And this is when I remind myself of a great benefit to my modern working method: My art is digital! And I can open up that file, ten or even twenty years later, and start tinkering to erase my own shameful history.

Or, better yet, flog myself properly for my former misdeeds by completely redrawing the thing.

As I have often said, even when asked not to, art is a two-stage process: 1) Create something so horrible that the shame of your own incompetence threatens to encourage suicide, and 2) Fix it. And I confess that I find fixing bad art a real pleasure. After all, the hard work of producing a piece of shit has already been done. Fixing it, especially after years of more sober judgment, is a comparative breeze.

I’ve done this heaps over the years, reworking old failures with the fervor of a CG-enabled George Lucas. Most recently, I revisited the challenge of Studs Terkel, whom I had originally rendered some ten or fifteen years ago as some long-forgotten illustration assignment.

If you don’t know Studs Terkel, conjure him up on Wikipedia, or better yet, dip into the online archive of his radio interviews, where you’ll find Studs interviewing a smorgasbord of cultural icons, working through the big questions of life. My only connection to Terkel, aside from admiring his work, has too many degrees of separation to qualify as a connection at all: I drew the 1992 Caliber Press comic book Portraits of Eddie, featuring stories told to me by my friend, Frank Licciardi, about the Chicago painter and musician Eddie Balchowsky, who was also a good friend of Studs. And no, you cannot see that comic because I drew it when I was twenty, and it looks horrible.

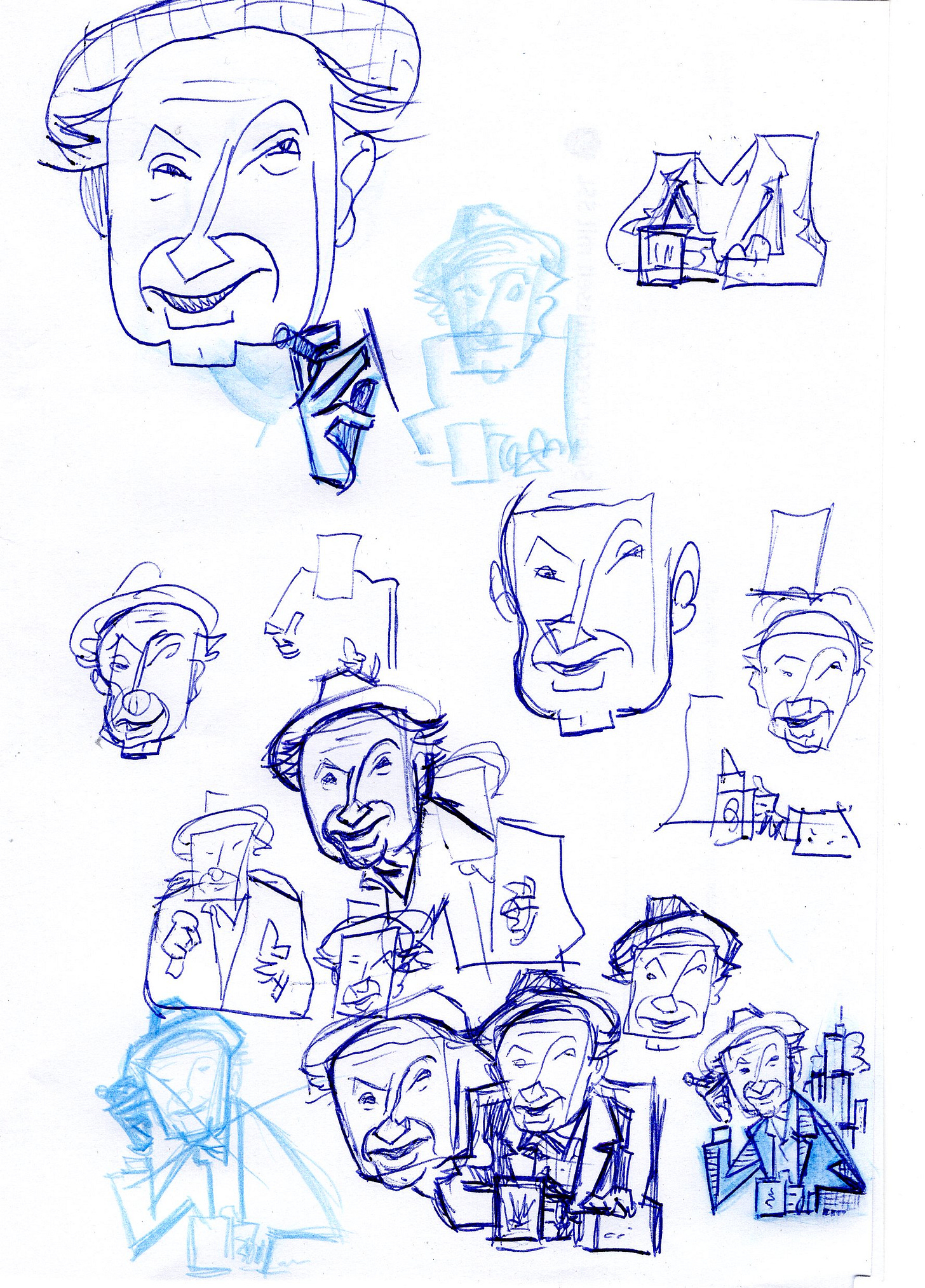

Maybe I’ll redraw that book someday, but in the meantime, I can rework my Studs. Granted, I don’t think the first version of the portrait is the absolute worst thing I’ve done (I’ll show you that one day when I’ve had a few drinks), but it ain’t good. It was clear that this was one of those cases where I just needed to start over, which meant printing out a fresh batch of photo reference as if I’d never drawn him before.

And this is where these mysteries come into play. How could I have looked at the same guy, in largely the very same photos, and come to such different conclusions? Was I impatient? Did I spend too much time hashing out the likeness in the original? Why couldn’t I have seen at the time that I was settling without having achieved Peak Studs? Why did I mistake poo for perfection?

And what the hell’s wrong with those of you looking at these and thinking, “Gee, I like the old one better?”

(And let’s not forget Ashley’s website, jam-packed with portraits and other drawings, his illustrated essay column, The Symptoms, his highly-affordable prints and books currently available, his eagerness for your portrait commission, and his contact email, thrdgll@gmail.com, where he longs to hear from you.)