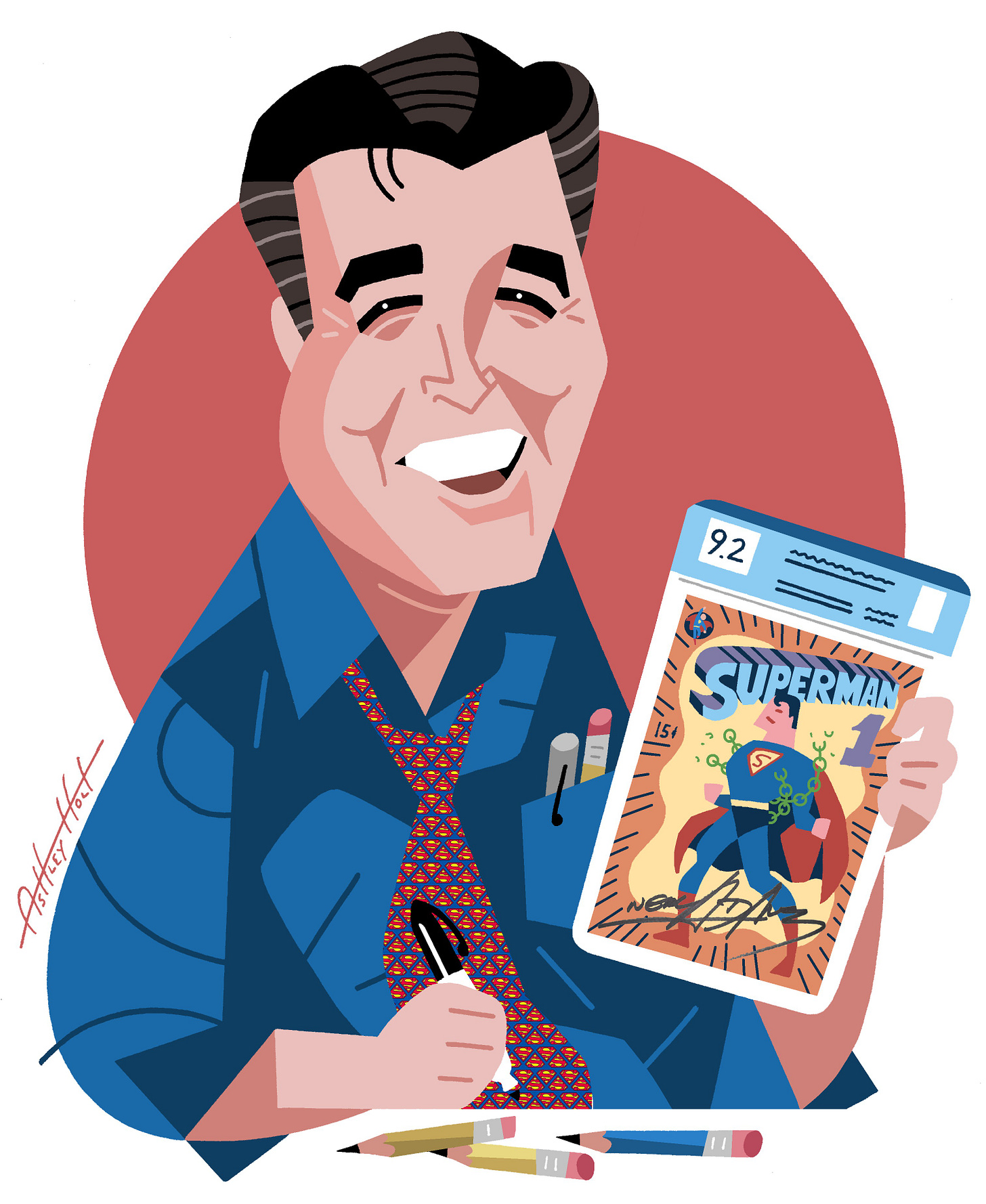

Adams' Nib

Neal Adams and the Passions of Fandom

Fair warning, civilians: This is an exceptionally geeky, “inside baseball” reverie.

From my earliest memory as a floor-dwelling infant, there was never a separation between my interest in comics and my desire to draw. Indeed, I’ve rarely met anyone in the world of comic book fandom who did not, at one time or another, express a desire to draw the Nightwings and Veronicas of their favorite comics, professionally or otherwise. Even today, despite the steady encroachment of Ai, comics remain a medium about real, by-hand drawing, and the quality of that drawing can make or break fan devotion. Yes, the fellows loitering in Warp Factor Comics and Games may engage in heated discussion about time tunnels, holodecks, and other scientific theory, but you can bet that the central concern among these dollar-boxers will be whether Todd McFarlane drew a cooler Batman cape than Bernie Wrightson.

As a pencil-pushing lifer myself, I take comfort in this. Comic books, sad as it may seem, are the last frontier of popular culture where drawing – the kind scratched out with pen, brush, and stylus – is a matter of serious aesthetic criticism. Animation and video games may receive praise for their “design,” but only in the world of comics is a single illustrator’s handcrafted renderings of kick-ass Spider-Man poses, with individual, stylistic personality, driving the industry. (Yes, you can get likes on Instagram for drawing, but this has as much commercial impact as Grandma posting it on the refrigerator.)

This has always been the case with comic books. Boys browsing the spinner racks of the Seventies inevitably launched into debates about Jack Kirby’s inkers, Rich Buckler’s swipes, Jim Starlin’s questionable anatomy, Frank Robbins’…Frank Robbinsness, and Gil Kane’s preoccupation with nostrils. I say boys because the girls of that era who passed the time with Archie and Little Audrey seemed able to do so without developing obsessive-compulsive disorders over crosshatching techniques. Serious comic book art connoisseurship was boy stuff, as only the male can fully appreciate the delicate foreshortening of Green Lantern’s bulging inner thigh. Make of that what you will.

As such, a certain type of drawing tends to thrill prepubescent boy Marvelites: detailed, tightly-rendered, “realistic,” effectively intense. Screaming melodrama is the key ingredient, complete with hyper-flexed musclemen, mouths agape in anguish, flexing explosively against some cosmic apocalypse or other. Artists who can deliver this with the most painstaking craftsmanship and the slickest style quickly become “fan favorites.” And for many, the essential fan favorite of the modern era was Neal Adams.

Adams, in his superhero art for Marvel and DC, introduced a level of ‘roid rage realism drastically different from the Curt Swan placidity we’d all grown accustomed to. His super characters flexed every tendon and artery, every tooth in their raging heads exquisitely detailed, every wind-swept hair displaying a will of its own. Adams’ art looks like a PCP overdose personified. Figures twist, thrust, and gyrate as if suffering the fires of the damned, all minutely over-rendered to a violent degree.

I hated it. To my infantile mind, Dick Sprang’s Batman of the 1950s was the ideal, living as he did in the same bold, minimal world of open color as Dick Tracy and Nancy. Something seemed to be terribly wrong with Adams’ Batman. He was encountering the same Joker booby traps and Riddler puzzles as always, but they seemed to be upsetting him disproportionately. In Adams’ handling, simply standing alone in the Batcave appeared to put Batman in a state not unlike being tortured with a car battery.

But fandom, be it for sports teams, polka bands, or famous pandas, is a complex condition. Over time, I was forced to reckon with the harsh truth that my “hating” Neal Adams constituted a weird form of anti-fan fandom. That is, I had to admit to myself that wallowing in the quirks of Neal’s unpleasant approach to drawing was bringing me quite a bit of joy. Not just ironic appreciation, not just snarky, so-bad-it’s-good superiority, but something much closer to genuine affection. There’s some convoluted reason that, after selling 99% of my comic book collection, one of the few books that I kept was Adams’ atrocious Skateman #1, a terrible idea very badly executed.1 (I kept a copy of Rob Liefeld’s Captain America #1 for similar reasons.)

What became clear is that Adams’ work had always given me a thrill, just not the sort he had intended. Maybe it’s just the softening of the heart that comes with nostalgia, but my lifelong irritation over Neal’s art, expressed with hot-blooded venom, loudly and often, qualifies today as a fond memory. Same with my “hatred” of Carmine Infantino, Syd Shores, or even the execrable Vince Colletta. That these unique stylists could inflame my passions so reliably speaks to the singularity of their personal brands, producing mannerisms of such eccentricity that they cannot be ignored.

And they did it all with lines on paper. Drawings. Like a toddler on the linoleum, scratching out his best Doc Ock in ballpoint and Crayola, dreaming of making a mark on the world of comics. And dammit, if moving people to rage with nothing but a pencil and bad taste isn’t a noble aspiration, I don’t know what is.

- A.H.

(And let’s not forget Ashley’s website, jam-packed with portraits and other drawings, his highly-affordable prints and books currently available, his eagerness for your portrait commission, and his contact email, thrdgll@gmail.com, where he longs to hear from you.)

I didn’t know until yesterday about Death to the Pee Wee Squad, Neal Adams’ motion picture directorial effort. I’m going to give Adams the benefit of believing this was a fun-time craft project for his family and friends, rather than a genuine bid for Hollywood infamy, but it’s almost Beast of Yucca Flats-level terrible. You might watch the movie, but you can’t see it – it’s filmed almost entirely in grainy darkness. I’d like to say hating it brought me pleasure, but I had a very difficult time sitting through it. It may be of novelty interest for old-time comics fans, since industry figures such as Denys Cowen, Larry Hama, Jack Sparling, and, swear to god, Gary Groth appear in the film. But really, you’d be better off reading Skateman, as unbelievable as that sounds.

Save for the Michelangelesque Jack Kirby I held most spinner-rack jobbers in snooty, critical contempt. Timeless genius was defined in every issue of MAD, the poor boy's 35 cent Louvre and national gallery, whereby Drucker, Davis, and Woodbridge descended from Mt Olympus to show we, the more critically discriminating 13 year old beggar children, what immortal draftsmanship looked like. Fistfights defended the honor of Davis over Drucker or vise-visa. My smeary pencil copies of Mort Drucker's Star Trek parody were not just amateur scratches but a sincere attempt to unite with the deity. JDA